' ' '

Atlantis Artist Spotlight

Luke Walters

'I Made the Invisible Man'

Winner of Best Live Action Short Film and Best Actress

Writer-director Luke Walters approaches genre as a space for restraint rather than spectacle, using familiar frameworks to explore control, authorship, and consequence. His short film I Made the Invisible Man concludes the “I Made” trilogy with a quiet precision that trusts performance, framing, and implication over explanation. Shot in stark black and white and built around absence as a narrative force, the film resists noise in favor of tension and reflection — inviting the audience to lean in rather than be overwhelmed. In this Atlantis Artist Spotlight, Walters reflects on authorship, collaboration, and the discipline required to let a film speak softly and linger long after it ends.

For readers meeting you for the first time, how would you introduce yourself in your own words?

I’m Luke Walters, a UK-based writer and director drawn to character-led genre storytelling — particularly stories that use familiar ideas to explore human behaviour in unexpected ways. My background is practical rather than academic. I came up through production, shooting, directing, and producing commercial, digital, and broadcast work.

Over the past few years, I’ve developed a body of independent work inspired by classic science fiction, approached through a grounded, performance-led lens. That journey became the “I Made” trilogy, beginning with I Made War of the Worlds and I Made the Time Machine, and concluding with I Made the Invisible Man.

Where the earlier films leaned into scale, Invisible Man is more interested in control and authorship. It deliberately resists spectacle, focusing instead on consequence, presence, and what happens when you trust the audience to lean in rather than be overwhelmed.

I Made the Invisible Man balances formal precision with restraint and humour. When did the core tone crystallise for you?

The tone crystallised when the project stopped trying to be a big homage and started trying to be sharp. The earliest version was much longer — around 45 to 50 minutes — built as an Edwardian-era murder-mystery weekend with a Scream-style engine. It was fun on paper, but it became clear that the strongest version of the film wasn’t the loudest one.

Once we committed to precision and restraint, everything fell into place. The humour became drier and more situational, coming from character behaviour rather than jokes. The visual approach became simpler and more deliberate. Early choices — controlled framing, letting scenes breathe, building tension through implication rather than explanation — locked in the tone. That’s when it stopped being a concept and started becoming a film.

The film often trusts suggestion over explanation. How did you decide where to leave space for the audience?

I treated the audience as an active participant rather than someone to be walked through the plot. If a film explains everything, it removes both tension and personal connection — the viewer has no work to do.

The guiding question was always: Do we need to state this, or can we make the viewer feel it? If a moment played emotionally and visually, I didn’t want to dilute it with extra lines or scenes that “clarified” the point. We focused on clear cause and effect, but allowed meaning to sit beneath the surface. That balance is where the film’s confidence comes from.

You served as writer, director, producer, cinematographer, and editor. Was that necessity, preference, or evolution?

It started as necessity and evolved into preference. Years working in broadcast and branded content force you to move quickly between roles. Over time, that became a creative advantage.

On this film, it allowed every department to pull in the same direction. I could write with the edit in mind, shoot with rhythm in mind, and make decisions quickly without losing intent. That “shooting for the edit” mindset saved time, protected performances, and kept the film cohesive. Invisible Man clarified that multi-hyphenate work isn’t about doing everything alone — it’s about creating harmony across the process.

How did you manage internal conflicts between roles?

I learned to separate what I like from what the film needs. That sounds simple, but it’s difficult when you’re wearing multiple hats.

If the director wanted a moment to play slower but the editor felt pacing slipping, the editor won. If the writer wanted explanation but the director knew the performance carried it, the director won. The film always had the final vote.

Practically, I relied on checks: watching cuts without sound to test clarity, revisiting edits after time away, and sharing versions with a small group I trust to tell me when something is self-indulgent or unclear. That kept me honest.

Was there a moment you consciously stepped back and trusted collaborators?

Yes — early on. We began shooting with a slightly different script. It read well, but rehearsals revealed that neither the actors nor I fully connected with it. Instead of forcing the plan, we rewrote in real time and adjusted the film to what was actually emerging on set.

That only works with trust. The shift improved the film quickly because performance became the compass rather than the page. It stopped being “the plan” and started being “the truth.”

How did you stage scenes where absence is the central visual idea?

When absence is the idea, you have to be intentional about what replaces it. Blocking, framing, negative space, eyelines, and reaction become the storytelling tools.

The camera never chases the trick. It behaves as if the invisible element is real, and the characters reveal it through behaviour. Clean composition, patient pacing, and repetition of visual language allow the audience to subconsciously learn the rules — and feel tension when those rules are tested.

How much of the film’s meaning was intentionally open during writing?

It was a mix. Clear thematic intentions were always there, but the film changed shape across drafts — from one place, to slasher-like structure, to ideas around AI, and finally into something closer to an erasure narrative.

What stayed defined was emotional intention and atmosphere. What stayed open was how much the film should explain itself. The openness isn’t vagueness — it’s an invitation.

The cinematography feels controlled without calling attention to itself. What rules guided it?

The goal was quiet control. We set rules around stability, simplicity, and consistency. This film couldn’t share the same language as the earlier two — Invisible Man needed containment.

We shot in Academy ratio and black and white. While there’s a nod to the 1933 Claude Rains Invisible Man, the decision was about discipline. The Academy frame compresses space, turning negative space into narrative space.

Black and white represents Victoria’s controlled, isolating world. Social media material appears in full-frame colour — the external reality audiences recognise. We return fully to colour only at the end, when Victoria stops resisting what her world has become.

Structurally, the first half is static — locked-off frames reflecting order and control. After the central revelation, the camera shifts to handheld. Not aggressively, but enough to introduce instability. Her world flips, and the film needs to feel that rather than announce it.

Consistency allows restraint to read as intention rather than limitation.

How did working with 1st AC Kieran Khalid support the film?

Kieran brought discipline and calm. When a film depends on precise framing and invisible presence, focus and consistency become storytelling tools.

Trusting him freed mental space on set. While directing performance and thinking about coverage, I knew the technical side was locked. That reliability gave the film confidence it couldn’t have achieved otherwise.

When did the edit reveal what the film wanted to be?

When we started removing the “help.” Early cuts often feel safer because they explain or soften intent. Once those beats were trimmed, the tone snapped into focus.

The edit became about rhythm and implication. If a scene landed emotionally, we moved on. That’s when the film revealed itself as lean, precise, and quietly unsettling.

Were there scenes you loved that had to go?

Not entire scenes — most restraint came from shaping moments within scenes. Timing, reduced exposition, trusting performance and framing. That allowed the film to stay tight without losing anything essential.

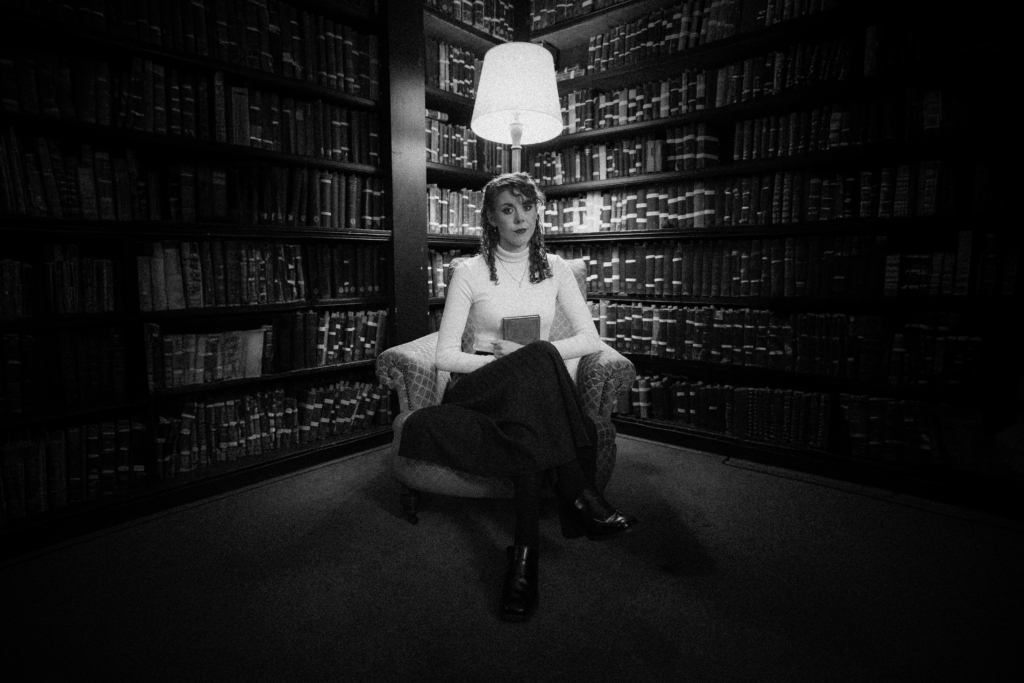

Elizabeth Coverdale — Best Actress Winner

How did you ground emotional reactions to absence?

Giving the character space to think and feel was key. I focused on understanding Victoria’s environment and emotional logic rather than presenting a generic response.

Drawing on her relationships with other characters helped define stakes. I was also inspired by Anne Brontë — often called the “forgotten Brontë” — whose work explored female emotion and strength long before it was recognised. That sense of injustice and suppressed fury resonated with Victoria.

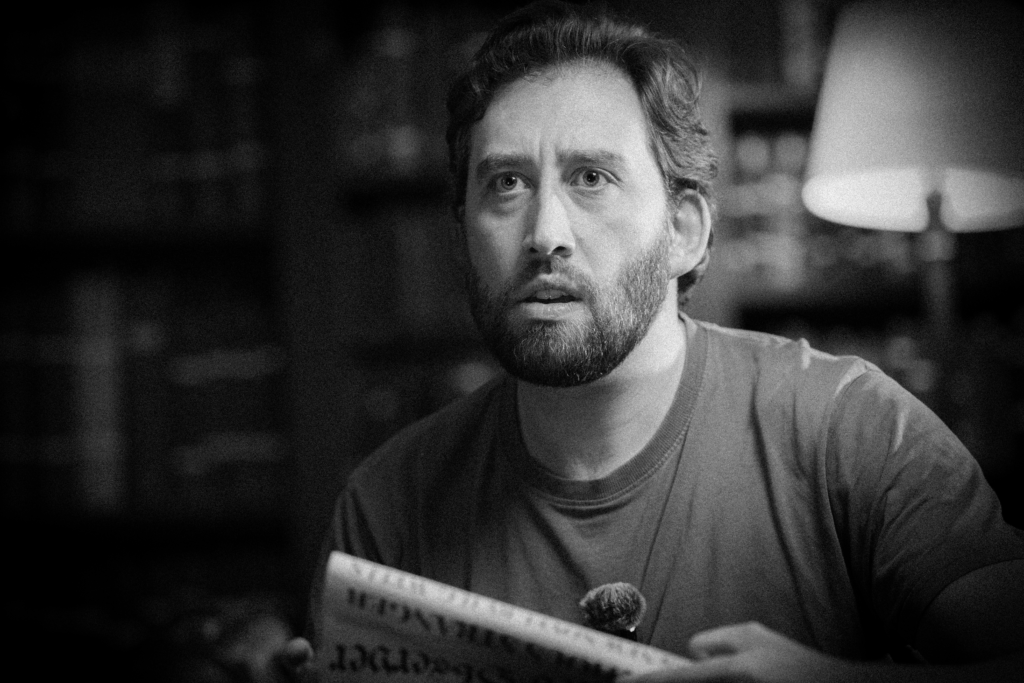

Jonathon Carley — Key Cast

How did you approach restraint in performance?

Preparation. Understanding who Julian is, what he wants, and how he relates to others allowed me to underplay without losing clarity.

The full Invisible Man costume removes facial expression and eye contact, which is challenging. There’s a temptation to overcompensate physically, but restraint felt more truthful. Julian exerts control through stillness.

As a voice actor, I’m used to channelling emotion through voice alone, which helped. When the mask finally comes off, the shift is physical and emotional — no theatrics, just vulnerability. That scene affected me deeply, largely because of Elizabeth’s performance and the trust within the team.

James Dorman — Key Cast

How did the ensemble develop a shared rhythm?

Making the third film together helped enormously. We know each other’s rhythms. Luke wrote the characters specifically for us, and we all shared similar sensibilities. From the start, we “got” the tone and how to support it collectively.

Has recognition changed how you relate to the film?

It still feels private. The film has won awards, but it hasn’t truly been seen yet. It’s only just starting its festival run.

Out of the trilogy, this is the one I revisit the least. Finishing it felt like closing a chapter. I’m proud it exists — now I want it to go out and do what it’s meant to do.

What do you hope audiences carry with them?

I don’t want applause. I want quiet. That reflective silence where people aren’t sure what they think yet, but know they felt something.

If it works, the film lingers — on the walk home. That’s the reaction I value most.

Has this project reshaped how you think about authorship?

Yes. Restraint isn’t the absence of ambition — it’s a form of ambition.

Even when I carry multiple roles, the best work still comes from honest collaboration. The film improved the moment we stopped protecting the plan and started responding to what was actually happening. Going forward, I want precision without rigidity.