' ' '

Atlantis Artist Spotlight

Shamsi Alilova

Screenwriter of

Best Feature Screenplay

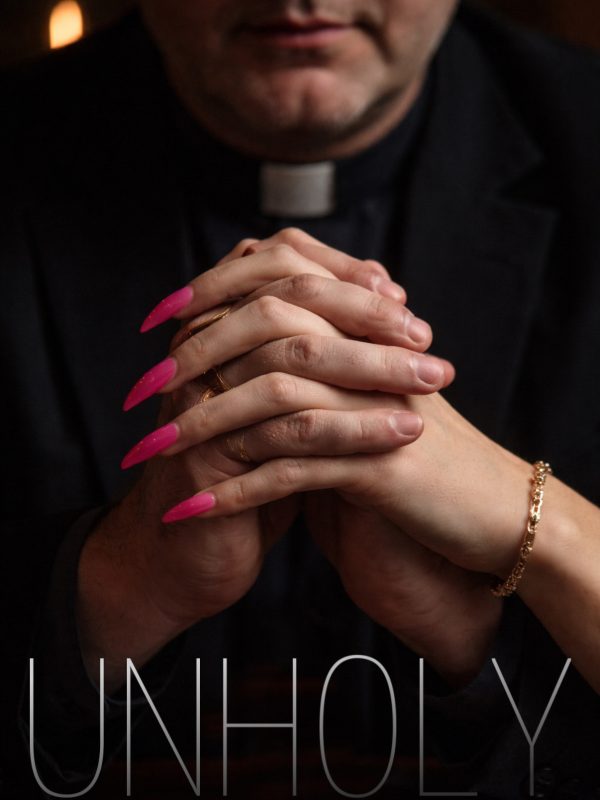

'Unholy'

For those encountering your work for the first time, how would you describe yourself as a storyteller?

I’m drawn to stories that live in the gray zone—where people are trying to do the right thing, but the ground beneath them is unstable. I tend to approach storytelling from a human, psychological angle, even when the world feels supernatural or morally charged. I’m less interested in clear answers than in emotional truth, and in the quiet moments where characters reveal who they are without realizing it.

When did this project first begin to take shape for you, and what initially drew you toward it?

The project began with a contrast that wouldn’t leave me alone: the image of public faith and private secrecy existing side by side. I was drawn to the idea of a figure who offers comfort, certainty, and moral clarity to others—while quietly unraveling himself. From there, the story grew outward, connecting belief, exploitation, fear, and the narratives people tell themselves in order to survive.

What made this the right project for you to pursue at this point in your creative life?

At this stage in my work, I’m less interested in spectacle and more interested in consequence. UNHOLY felt like an opportunity to slow down and sit with discomfort—to trust restraint, silence, and implication rather than explanation. It also allowed me to explore moral complexity without prescribing judgment, which feels increasingly important to me as a storyteller.

The work engages with belief, fear, and moral tension. Were you more interested in exploring answers, or in staying within uncertainty?

Very much uncertainty. I don’t think belief systems collapse because of one clear revelation—they erode through doubt, contradiction, and silence. I wanted the story to live in that erosion. The tension comes not from proving who is right or wrong, but from watching people struggle to hold onto meaning as their internal logic begins to fail.

How did you think about balancing internal, psychological conflict with external narrative momentum?

The external plot—the blackmail, the investigation, the threat—is intentionally simple. Its function is to apply pressure. What really drives the story is how each character reacts under that pressure: who lies, who rationalizes, who breaks. I tried to let psychological shifts dictate pacing rather than relying on constant plot escalation.

Atmosphere plays a strong role in how the story unfolds. How intentional was your use of tone, restraint, or silence as narrative tools?

Extremely intentional. Silence, in particular, felt thematically essential—unanswered prayers, unspoken truths, things left unsaid. I wanted the atmosphere to feel heavy but controlled, so that even small disruptions would carry weight. Horror here isn’t loud; it seeps in quietly.

Were there particular influences—cinematic, literary, philosophical, or personal—that helped shape the world of this piece?

There were influences ranging from psychological thrillers to slow-burn horror, but more than specific references, I was influenced by real-world contradictions—public virtue versus private behavior, and the way charisma can blur moral accountability. Philosophically, I was interested in the idea that evil doesn’t always announce itself; sometimes it hides behind comfort and good intentions.

Ambiguity feels central to the experience. What do you hope audiences sit with once the story ends?

I hope audiences sit with unease rather than resolution—with questions about complicity, power, and self-deception. I don’t want them asking, “Who was the bad guy?” so much as, “Where did things go wrong—and how quietly did it happen?”

Did any characters evolve in unexpected ways during the writing process?

Yes—particularly Nathan. What surprised me was how human he became the more I resisted judging him on the page. Allowing him moments of tenderness alongside manipulation made him far more unsettling, and more truthful. The same is true for secondary characters, who often revealed their own moral compromises without needing explicit focus.

What aspects of the project were the most challenging to articulate on the page, and why?

Restraint was the hardest part. It’s tempting to explain everything or spell out characters’ motivations, but this story needed less explanation, not more. I had to let scenes unfold naturally and allow moments of discomfort to remain unresolved. That restraint was challenging—but essential.

There’s a strong sense of moral friction rather than clear judgment. How conscious was that choice?

Very conscious. I’m not interested in moral binaries. Judgment can distance an audience; friction invites them in. I wanted viewers to feel implicated—to recognize how easily they might empathize, excuse, or look away.

Was there a specific scene or breakthrough that helped unlock the rest of the story for you?

The breakthrough moment comes when Nathan agrees to hand over the money (Phillips 66). Up until this point, he still has options: he could deny, fight back, or seek help. By paying, he resolves nothing through words—he confirms his guilt through action. This is the moment he loses any moral high ground. He becomes a prisoner of the system, no longer just a pastor. It’s where the mask of the “man of God” finally cracks completely.

How do you hope different viewers or readers might interpret the same material in different ways?

I welcome contradictory readings. At its core, the film invites reflection on knowing when to stop—before desire turns into destruction. Some may see it as a critique of institutional faith; others as a personal tragedy, or a cautionary tale about power and exploitation. All of those interpretations can coexist. The story isn’t meant to instruct or moralize—it’s meant to provoke.

Looking back now, is there anything about the finished work that surprised you?

I was surprised by how emotionally restrained it became. I expected something darker in a more overt way, but what lingered instead was sadness—the quiet cost of deception on everyone involved. That felt honest.

Where can audiences go to follow your work or stay connected with what you’re creating next?

Audiences can follow my work through upcoming festival screenings and future projects currently in development. This story is part of a larger exploration I’m continuing—focused on belief, power, and mystery. I’m also on Instagram at @fulana000000.